There is Nothing to Forgive: Everything Has its Reason

It’s a cold December day in 1964. You are in the U.S. Army, stationed overseas, eager to board your flight later that day to come back home for Christmas. As you wait for the “hop,” you meet a stranger and head into the local town to grab a quick bite. You realize this person has no means to buy a meal, and you begrudgingly offer to buy it…and several drinks, for both of you, suspicious that the person befriended you for this purpose. You ultimately miss your flight.

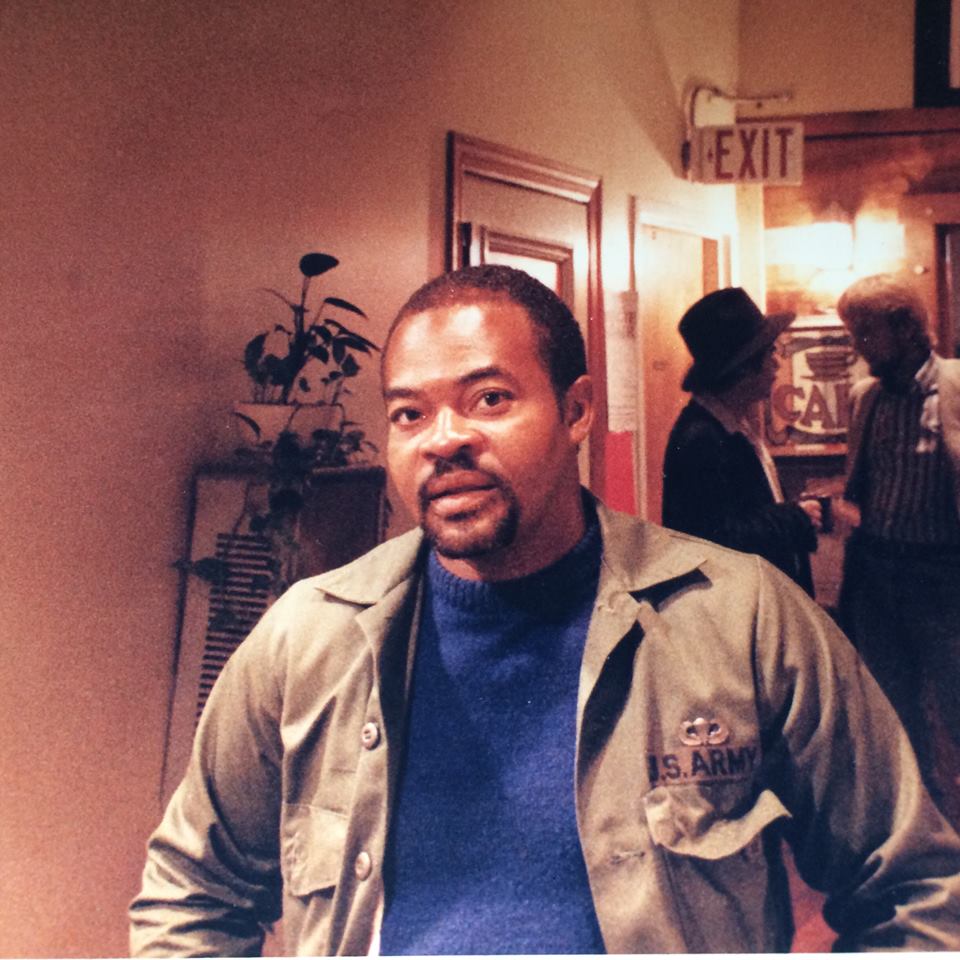

Faulting the stranger, James Floyd was annoyed he was delayed an additional day. At that point in his life, Floyd was annoyed about a lot of things. He was discharged from the Army a few years later and returned to his hometown of Nashville, Tennessee to begin two careers: one as a writer and one as a criminal.

The criminal lifestyle naturally led Floyd down a destructive path: he hurt everyone around him–family, friends, strangers, and himself. He lived the life of an addict. On one occasion, he got into a violent altercation with his own father–an experience that would later torment him.

In 1973, he was arrested and charged with bank robbery, and ultimately convicted in 1974. He was incarcerated at Riverbend Maximum Security until 1976, then paroled to Atlanta Fed, and released in 1978. While incarcerated, Floyd rediscovered and realized his writing ability, where college-level classes were offered.

One year, two U.S. Marshals escorted him to a hospital, where his father lay dying. Tormented by the pain he had caused, Floyd begged his father for forgiveness, to which his father smiled and replied, “There is nothing to forgive.” Floyd tears up when recalling the unconditional love of his father.

One year, two U.S. Marshals escorted him to a hospital, where his father lay dying. Tormented by the pain he had caused, Floyd begged his father for forgiveness, to which his father smiled and replied, “There is nothing to forgive.” Floyd tears up when recalling the unconditional love of his father.

Upon his release from prison–and for the next ten years–Floyd sought peace through bottles and needles, until his body could no longer retain solid foods. His mother begged him to get help. As he waited for the bus to a treatment center in Madison, he contemplated using his few remaining dollars for one last binge, instead buying a hot dog, chips, and a soda.

His greatest fear was that by surrendering his will, he would lose his ability to write. Instead, James has honed his talent in tandem with what he would call his spiritual recovery–for the last 29 years. His first book, Some Gentle Moving Thing, has reached readers worldwide. James also works directly with others in recovery and seeking recovery, as well as with local inmates, offering counsel through the sharing of experience, strength, and hope. But, as James might tell you, his life is not one of redemption as depicted by Hollywood. Rather, his life of recovery requires constant contact with what he refers to as his Higher Power, daily meditations, confronting personal fears, remaining teachable, and offering assistance where opportunities present themselves.

In his creative writing classes, James encourages students to identify, explore, and define the relationships being articulated in their art. As a person who becomes familiar with his style, you might often find him discussing the same ideas in writing classes as well as in the context of recovery. James believes his art and life are works-in-progress.

James is committed to passing along what he has learned from others. He believes it is not for us, as humans, to fully realize the effects of our kindness to others; rather–we must simply focus on being kind.

As James concluded his story about missing the flight from Germany to New York in 1964, he laughed about being annoyed with buying the stranger food and drink. He recounted what he discovered upon landing in New York the next day: “The plane I missed had crashed into the side of a mountain, killing all the passengers. The stranger I had met was not on that plane, nor on the plane I was on the next day, and I never heard from him again.” Somewhat embarrassed by his initial resentment towards the stranger for delaying his flight, James says, “There is nothing to forgive.”

Get inspired

Comments No comments